In Memoriam

10.12.09

Goodbye, Mr. Penn

By GREG POND

By GREG PONDHow do you say goodbye to someone you never met?

I never knew Irving Penn. But I'm going to miss him. He was a constant, important presence in my life for many years.

I've looked for Irving Penn's pictures in American Vogue every month for as long as I can remember. I looked for the man himself on the street in New York too. A photographer friend once told me a story about Mr. Penn, a myth no doubt, one of those artist-as-God stories, related in a hushed voice, but I liked the story, so I chose to believe it.

The story went that after Mr. Penn's brother, the director Arthur Penn, became enormously successful with his film Bonnie and Clyde, Irving Penn, in a fit of sibling rivalry, became depressed. As the story was told, Mr. Penn walked around New York, his head bowed low. It was during one of these somber strolls that he first noticed the rubbish - cigarette butts, discarded food containers, crushed paper cups, and flattened work gloves. The urban trash gave the master photographer an idea to make still lifes of this "Street Material." I didn't really believe the story. The dates didn't match, and it was just too good to be true, but nonetheless, I loved it. And I loved those pictures! Those gorgeous platinum still lifes are some of the most beautiful pictures anyone has ever made. I knew Mr. Penn's studio was on lower Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. So whenever I was in his neighborhood I would keep my eyes peeled for an elegant older gentleman walking with his head bowed. I never saw Mr. Penn of course, although I saw quite a few other men walking around (sometimes talking to themselves) looking for cigarette butts on the street.

Other people can and will write about Irving Penn's work with more expertise than me. Art critics, editors at Vogue, curators, photographers, friends, and gallerists will write intelligently about his work, his technique, what he was like as a person, and how he made his extraordinary pictures. I can't explain the technical aspects of platinum printing, what made Mr. Penn laugh, or exactly how he lit his subjects. All I can write about is what it's been like working as a magazine photo director knowing that the person I believed to be the greatest living photographer was still, in his 90's, shooting magnificent pictures for magazines every month. All I can write about is what his work meant to me.

Mister Penn. You never heard anyone ever say "Irving." Names such as: Dick, Annie, Herb, Mario, Steven, Mary-Ellen, Bruce, and Helmut bounce off the walls at Conde Nast. But everyone called him Mister Penn. He was on another level. Art directors, photo editors, photographers, and fashion editors had a respect for him that they didn't have for other photographers. People in the magazine business, and in the world of photography didn't simply admire him; they were in awe of him. He was one of my great heroes.

It was exciting that he made his pictures for magazines. A magazine. American Vogue to be precise. When I started working at Conde Nast as a lowly photo assistant at GQ in 1987, it was thrilling that the company that paid me to work in photography (admittedly on a vastly different pay scale, answering phones and running to the stat room - yes, stat room) also employed Mr. Penn. I felt like I was working at a film studio where a great director like Hitchcock was making movies. I was excited and proud to be in the same business as the master.

Irving Penn's work for Vogue was an important part of the reason that magazine photography in the 20th century commanded respect, and was taken seriously. He made dazzling pictures that not only held a mirror to the culture; they came to define the culture as well. And he was a dedicated magazine photographer. He was committed to Vogue and Vogue was committed to him. So many other talented photographers worked for magazines at one point in their careers but then stopped to focus exclusively on making pictures for books, galleries, and museums. Some giants of photography, Robert Frank for example, abandoned photography altogether to make films. But Mr. Penn never stopped making pictures for Vogue. His career started and ended with Vogue. Month after month, he delivered the most elegant, intelligent, and strongest magazine pictures anyone had ever made. His work was proof that magazine photography could exist as art.

And what photography! His Picasso portrait from 1957 is an elegant masterpiece. The great photographer with the amazing eye photographed the amazing eye of the great artist. Mr. Penn brilliantly turned the painter into a Minotaur. The portrait of Jasper Johns that he made for The New Yorker in 1996 is stunning. Johns sitting with his shoulders hunched, his gaze defiant, looking old and frail, yet intense and alive. And in all seriousness, I cannot look at frozen food in the supermarket without thinking of Mr. Penn. That simple, clever still life of blocks of frozen peas and asparagus is the most perfect magazine still life photograph I've ever seen.

Virtually everyone who made a brilliant movie (Ingmar Bergman, 1964), wrote a great book (Truman Capote, 1948, one of three sittings), painted an important painting (Willem de Kooning, 1983), designed a beautiful fashion collection (Yves St. Laurent, 1957 and 1984), or woke up looking beautiful every morning (Kate Moss, 1996) was photographed by Mr. Penn. Not to mention the motorcycle cops, tribesmen, presidents, poets, models, debutantes, rock stars, butchers and bikers. He photographed frog's legs, ballet dancer's legs, opera singers and everyone and everything in between. The volume of work is staggering. And there's not a throwaway picture in the bunch. Irving Penn was not a mail-it-in kind of photographer.

At the end of Mr. Penn's life, I would say to people: You know, Irving Penn is in his 90's and he's still shooting. And they'd say: Really? I didn't know he was still alive. After we all emailed, and texted, and Twittered last week about Mr. Penn's death, people said: "It's so sad." I thought: No it's not. Irving Penn was 92 when he died. He made amazing pictures until the end. Sixty years is not a bad run.

I will miss Irving Penn's pictures. I will miss going to the newsstand every month and getting my mind blown by an insanely brilliant portrait shot against a simple back drop, or a clever still life. I will miss seeing new Irving Penn pictures. I will miss opening up Vogue at a newsstand and seeing a Penn photograph that stands the hair up on the back of my neck and wanting to show it to the guy at the counter and shout: "Oh My God! Look at this amazing picture!"

The newsstand won't look any different in six months, or in a year. There might be a few less magazines, but essentially it will look like the same place you go to now. Vogue won't look any different at first glance either. But after a while you might notice that something is missing - something elegant, classic, witty and urbane. Something beautiful, simple, and fiercely intelligent won't be there anymore.

How do you say goodbye to someone you never met? I'm sad I never got the chance to shake his hand. I know I'll never walk around 5th Avenue and 17th Street in Manhattan and not keep an eye out for a man looking down at the sidewalk. A man people called Mister Penn.

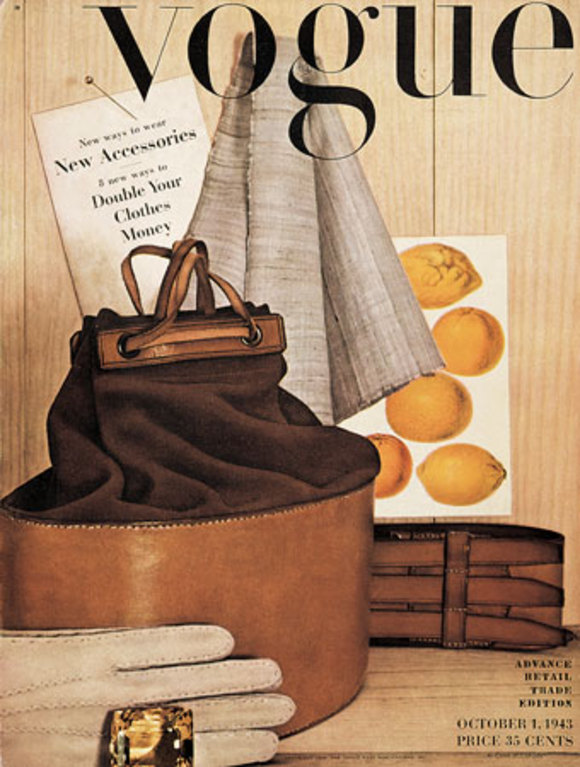

The Vogue cover above is from the October 1, 1943 issue; Photographer, Irving Penn, Art Director, Alexander Liberman.

RELATED:

Mr. Penn's obituary from The New York Times.

A slideshow of Mr. Penn's work, also from the Times.

A description of how Mr. Penn's first cover for Vogue, in October of 1943 and featured above, came to be, and a gallery of Penn's Vogue images, courtesy of Fashionologie.